Lucas Paradox

Release Date: 5//1990

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: Capital is not flowing from developed countries to developing countries despite the fact that developing countries have lower levels of capital per worker, and therefore higher returns to capital. Authored by Robert Emerson Lucas, Jr..

Description: In economics, the Lucas paradox or the Lucas puzzle is the observation that capital does not flow from developed countries to developing countries despite the fact that developing countries have lower levels of capital per worker. Classical economic theory predicts that capital should flow from rich countries to poor countries, due to the effect of diminishing returns of capital. Poor countries have lower levels of capital per worker -- which explains, in part, why they are poor. In poor countries, the scarcity of capital relative to labor should mean that the returns related to the infusion of capital are higher than in developed countries. In response, savers in rich countries should look at poor countries as profitable places in which to invest. In reality, things do not seem to work that way. Surprisingly little capital flows from rich countries to poor countries. This puzzle, famously discussed in a paper by Robert Lucas in 1990, is often referred to as the "Lucas Paradox."

Mandelbrot set

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: A particular set of complex numbers that has a highly convoluted fractal boundary when plotted.

Description: A particular set of complex numbers that has a highly convoluted fractal boundary when plotted. The set is closely related to the idea of Julia sets, which produce similarly complex shapes. Its definition and name are due to Adrien Douady, in tribute to the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot.[1] Mandelbrot set images are made by sampling complex numbers and determining for each whether the result tends towards infinity when a particular mathematical operation is iterated on it. Treating the real and imaginary parts of each number as image coordinates, pixels are colored according to how rapidly the sequence diverges, if at all.

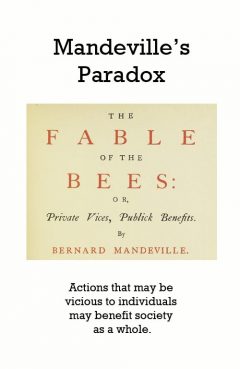

Mandeville's Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: Actions that may be vicious to individuals may benefit society as a whole.

Description: Shows that actions which may be qualified as vicious with regard to individuals have benefits for society as a whole. This is already clear from the subtitle of his most famous work, The Fable of The Bees: Private Vices, Publick Benefits. He states that "Fraud, Luxury, and Pride must live; Whilst we the Benefits receive.") (The Fable of the Bees, The Moral). The philosopher and economist Adam Smith opposes this (although he defends a moderated version of this line of thought in his theory of the invisible hand), since Mandeville fails, in his opinion, to distinguish between vice and virtue (The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Part VII, Section II, Chapter 4 (Of licentious systems)).

Masked Man Paradox

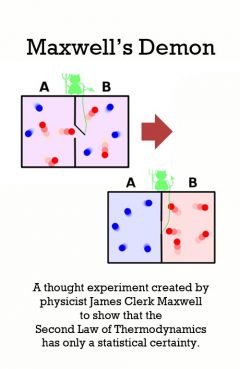

Maxwell's Demon

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: In the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics, Maxwell's demon is a thought experiment created by the physicist James Clerk Maxwell to "show that the Second Law of Thermodynamics has only a statistical certainty."

Description: In the philosophy of thermal and statistical physics, Maxwell's demon is a thought experiment created by the physicist James Clerk Maxwell to "show that the Second Law of Thermodynamics has only a statistical certainty".[1] It demonstrates Maxwell's point by hypothetically describing how to violate the Second Law: a container of gas molecules at equilibrium, is divided into two parts by an insulated wall, with a door that can be opened and closed by what came to be called "Maxwell's demon". The demon opens the door to allow only the faster than average molecules to flow through to a favored side of the chamber, and only the slower than average molecules to the other side, causing the favored side to gradually heat up while the other side cools down, thus decreasing entropy.

Meditation Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: The amplitude of heart rate oscillations during meditation was significantly greater than in the pre-meditation control state and also in three non-meditation control groups.

Description: The amplitude of heart rate oscillations during meditation was significantly greater than in the pre-meditation control state and also in three non-meditation control groups.

Meno's Paradox (Learning Paradox)

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: A man cannot search either for what he knows or for what he does not know. Authored by Plato.

Description: Meno's Paradox (Learning Paradox) Socrates brings Meno to aporia (puzzlement) on the question of what virtue is. Meno responds by accusing Socrates of being like a torpedo ray, which stuns its victims with electricity. Socrates responds that the reason for this comparison is that Meno, a "handsome" man, is inviting counter-comparisons because of his own vanity, and Socrates tells Meno that he only resembles a torpedo fish if it numbs itself in making others numb, and Socrates is himself ignorant of what virtue is. Meno then proffers a paradox: "And how will you inquire into a thing when you are wholly ignorant of what it is? Even if you happen to bump right into it, how will you know it is the thing you didn't know?" Socrates rephrases the question, which has come to be the canonical statement of the paradox: "[A] man cannot search either for what he knows or for what he does not know[.] He cannot search for what he knows -- since he knows it, there is no need to search -- nor for what he does not know, for he does not know what to look for."

Mere Addition Paradox (Parfit's Paradox)

Release Date: //1984

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: Is a large population living a barely tolerable life better than a small, happy population? Authored by Derek Parfit.

Description: Mere Addition Paradox (Parfit's Paradox) The mere addition paradox, also known as the repugnant conclusion, is a problem in ethics, identified by Derek Parfit, and appearing in his book, Reasons and Persons (1984). The paradox identifies an inconsistency between four seemingly true beliefs about the relative value of populations.

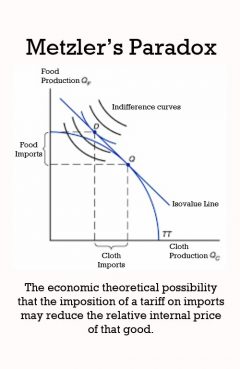

Metzler Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: The imposition of a tariff on imports may reduce the relative internal price of that good. Authored by Lloyd Metzler.

Description: In economics, the theoretical possibility that the imposition of a tariff on imports may reduce the relative internal price of that good. It was proposed by Lloyd Metzler in 1949 upon examination of tariffs within the Heckscher-Ohlin model.[2] The paradox has roughly the same status as immiserizing growth and a transfer that makes the recipient worse off.[3] The strange result could occur if the exporting country's offer curve is very inelastic. In this case, the tariff lowers the duty-free cost of the price of the import by such a great degree that the effect of the improvement of the tariff-imposing countries' terms of trade on relative prices exceeds the amount of the tariff. Such a tariff would not protect the industry competing with the imported goods.

Mexican Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: Mexican children tend to have higher birth weights than can be expected from their socio-economic status.

Description: Mexican children tend to have higher birth weights than can be expected from their socio-economic status.

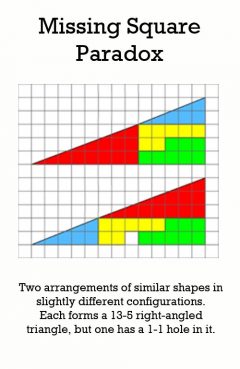

Missing Square Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message:

Description: The missing square puzzle is an optical illusion used in mathematics classes to help students reason about geometrical figures, or rather to teach them to not reason using figures, but only using the textual description thereof and the axioms of geometry. It depicts two arrangements made of similar shapes in slightly different configurations. Each apparently forms a 13-5 right-angled triangle, but one has a 1-1 hole in it.

Mocanu's Velocity Composition Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: A paradox in special relativity.

Description: Mocanu's Velocity Composition Paradox Since in general u v v u this raises the question as to which velocity is the real velocity.[4] The paradox is resolved as follows.[5] There are two types of Lorentz transformation: boosts which correspond to a change in velocity, and rotations. The outcome of a boost followed by another boost is not a pure boost but a boost followed by or preceded by a rotation (Thomas precession). So unlike Galilean composite transformations, in special relativity, boost composition is parameterized not by velocities alone, but by velocities and orientations, so u v and v u both describe correctly but partially the boost composition B(u)B(v).

Monty Hall Problem

Release Date: //1975

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: A game show, and choice of three doors: Behind one is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick door No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice? Authored by Steve Selvin.

Description: The Monty Hall problem is a probability puzzle, loosely based on the American television game show Let's Make a Deal and named after its original host, Monty Hall. The problem was originally posed in a letter by Steve Selvin to the American Statistician in 1975 (Selvin 1975a), (Selvin 1975b). It became famous as a question from a reader's letter quoted in Marilyn vos Savant's "Ask Marilyn" column in Parade magazine in 1990 (vos Savant 1990a): Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice? Vos Savant's response was that the contestant should switch to the other door. (vos Savant 1990a) The argument relies on assumptions, explicit in extended solution descriptions given by Selvin (1975a) and by vos Savant (1991a), that the host always opens a different door from the door chosen by the player and always reveals a goat by this actionbecause he knows where the car is hidden. Leonard Mlodinow stated: "The Monty Hall problem is hard to grasp, because unless you think about it carefully, the role of the host goes unappreciated." (Mlodinow 2008) Contestants who switch have a 2/3 chance of winning the car, while contestants who stick have only a 1/3 chance. One way to see this is to notice that there is a 2/3 chance that the initial choice of the player is a door hiding a goat. When that is the case, the host is forced to open the other goat door, and the remaining closed door hides the car. "Switching" only fails to give the car when the player had initially picked the door hiding the car, which only happens one third of the time. Many readers of vos Savant's column refused to believe switching is beneficial despite her explanation. After the problem appeared in Parade, approximately 10,000 readers, including nearly 1,000 with PhDs, wrote to the magazine claiming vos Savant was wrong (Tierney 1991). Even when given explanations, simulations, and formal mathematical proofs, many people still do not accept that switching is the best strategy (vos Savant 1991a). Paul Erd s, one of the most prolific mathematicians in history, remained unconvinced until he was shown a computer simulation confirming the predicted result (Vazsonyi 1999). The Monty Hall problem has attracted academic interest from the surprising result and simple formulation. Variations of the Monty Hall problem are easily made by changing the implied assumptions, creating drastically different consequences. If Monty only offers the contestant a chance to switch when having initially chosen the car, then the contestant should never switch. If Monty opens another door randomly and happens to reveal a goat, then it makes no difference (Rosenthal, 2005a), (Rosenthal, 2005b). The problem is a paradox of the veridical type, because the correct result (you should switch doors) is at first sight ludicrous, but is nevertheless demonstrably true. The Monty Hall problem is mathematically closely related to the earlier Three Prisoners problem and to the much older Bertrand's box paradox.

Moore's Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: "It's raining, but I don't believe that it is." Authored by G. E. Moore.

Description: Concerns the apparent absurdity involved in asserting a first-person present-tense sentence such as, "It's raining but I don't believe that it is raining" or "It's raining but I believe that it is not raining." The first author to note this apparent absurdity was G.E. Moore.[1] These 'Moorean' sentences, as they have become known, are paradoxical in that while they appear absurd, they nevertheless: can be true, are (logically) consistent, and moreover are not (obviously) contradictions. The term 'Moore's Paradox' is attributed to Ludwig Wittgenstein, who considered the paradox Moore's most important contribution to philosophy. Wittgenstein wrote about the paradox extensively in his later writings, which brought Moore's Paradox the attention it would not have otherwise received. Moore's Paradox has also been connected to many other of the well-known logical paradoxes including, though not limited to, the liar paradox, the knower paradox, the unexpected hanging paradox, and the Preface paradox. There is currently no generally accepted explanation of Moore's Paradox in the philosophical literature. However, while Moore's Paradox remains a philosophical curiosity, Moorean-type sentences are used by logicians, computer scientists, and those working in the artificial intelligence community as examples of cases in which a knowledge, belief, or information system is unsuccessful in updating its knowledge/belief/information store in light of new or novel information.

Moral Paradox

Moravec's Paradox

Release Date: //1998

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: Logical thought is hard for humans and easy for computers, but picking a screw from a box of screws is an unsolved problem. Authored by Hans Moravec.

Description: The discovery by artificial intelligence and robotics researchers that, contrary to traditional assumptions, high-level reasoning requires very little computation, but low-level sensorimotor skills require enormous computational resources. The principle was articulated by Hans Moravec, Rodney Brooks, Marvin Minsky and others in the 1980s. As Moravec writes, "it is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult level performance on intelligence tests or playing checkers, and difficult or impossible to give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility." Linguist and cognitive scientist Steven Pinker considers this the most significant discovery uncovered by AI researchers. In his book The Language Instinct, he writes: The main lesson of thirty-five years of AI research is that the hard problems are easy and the easy problems are hard. The mental abilities of a four-year-old that we take for granted recognizing a face, lifting a pencil, walking across a room, answering a question in fact solve some of the hardest engineering problems ever conceived... As the new generation of intelligent devices appears, it will be the stock analysts and petrochemical engineers and parole board members who are in danger of being replaced by machines. The gardeners, receptionists, and cooks are secure in their jobs for decades to come. Marvin Minsky emphasizes that the most difficult human skills to reverse engineer are those that are unconscious. "In general, we're least aware of what our minds do best," he writes, and adds "we're more aware of simple processes that don't work well than of complex ones that work flawlessly."

Morton's Fork

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: Choosing between unpalatable alternatives. Authored by John Morton.

Description: Morton's Fork A Morton's Fork is a specious piece of reasoning in which contradictory arguments lead to the same (unpleasant) conclusion. It is said to originate with the collecting of taxes by John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury in the late 15th century, who held that a man living modestly must be saving money and could therefore afford taxes, whereas if he was living extravagantly then he was obviously rich and could still afford them. Elected officers (members of parliament and councillors) sometimes may have recourse to a variant on Morton's Fork when dealing with unhelpful un-elected officers, or civil servants. This variant asserts that an un-elected officer's non-compliance with the directive of their elected officer must be due to one of two equally unacceptable causes: either the civil servant is lazy or incompetent, or the civil servant is acting willfully or maliciously against the instructions given by his or her elected officer. "Morton's fork coup" is a maneuver in the game of bridge that uses the principle of Morton's Fork.

The Mott Problem

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: Spherically symmetric wave functions, when observed, produce linear particle tracks. Authored by Sir Nevill Francis Mott.

Description: In quantum mechanics, the Mott problem is a paradox that illustrates some of the difficulties of understanding the nature of wave function collapse and measurement in quantum mechanics. The problem was first formulated in 1929 by Sir Nevill Francis Mott and Werner Heisenberg, illustrating the paradox of the collapse of a spherically symmetric wave function into the linear tracks seen in a cloud chamber.:119ff In practice, virtually all high energy physics experiments, such as those conducted at particle colliders, involve wave functions which are inherently spherical. Yet, when the results of a particle collision are detected, they are invariably in the form of linear tracks (see, for example, the illustrations accompanying the article on bubble chambers). It is somewhat strange to think that a spherically symmetric wave function should be observed as a straight track, and yet, this occurs on a daily basis in all particle collider experiments. A related variant formulation was given in 1953 by Mauritius Renninger, and is now known as Renninger's negative-result gedanken experiment. In this formulation, it is noted that the absence of a particle detection can also constitute a quantum measurement; namely, that a measurement can be performed even if no particle whatsoever is detected.

Movement Paradox

Release Date: //

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: In transformational linguistics, there are pairs of sentences in which the sentence without movement is ungrammatical while the sentence with movement is not.

Description: A phenomenon of grammar that challenges the transformational approach to syntax. The importance of movement paradoxes is emphasized by those theories of syntax (e.g. Lexical Functional Grammar, Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Construction Grammar, most dependency grammars) that reject movement, i.e. the notion that discontinuities in syntax are explained by the movement of constituents.

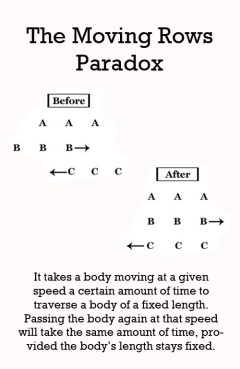

The Moving Rows (The Stadium)

Release Date: //-460

Country of Release:

Length:

MPAA:

Medium: Paradox

Genre:

Release Message: It takes a body moving at a given speed a certain amount of time to traverse a body of a fixed length. Passing the body again at that speed will take the same amount of time, provided the body's length stays fixed. Authored by Zeno.

Description: It takes a body moving at a given speed a certain amount of time to traverse a body of a fixed length. Passing the body again at that speed will take the same amount of time, provided the body's length stays fixed. Zeno challenged this common reasoning. According to Aristotle (Physics, Book VI, chapter 9, 239b33-240a18), Zeno considered bodies of equal length aligned along three parallel racetracks within a stadium. One track contains A bodies (three A bodies are shown below); another contains B bodies; and a third contains C bodies. Each body is the same distance from its neighbors along its track. The A bodies are stationary, but the Bs are moving to the right, and the Cs are moving with the same speed to the left. From Aristotle: concerning the two rows of bodies, each row being composed of an equal number of bodies of equal size, passing each other on a race-course as they proceed with equal velocity in opposite directions, the one row originally occupying the space between the goal and the middle point of the course and the other that between the middle point and the starting-post. This involves the conclusion that half a given time is equal to double that time. For an expanded account of Zeno's arguments as presented by Aristotle, see Simplicius' commentary On Aristotle's Physics.